A Pope’s Holy War

By quoting a 14th-century Christian emperor on an ‘evil and inhuman’ Islam, Benedict XVI ignites a global storm. What was he thinking?

By Jon Meacham

Newsweek

Sept. 25, 2006 issue - The setting was familiar, the occasion, the speaker thought, fitting. At three in the afternoon last Tuesday, after a quick ride from lunch in the Popemobile, Benedict XVI began a lecture in the Aula Magna of the University of Regensburg in Germany. As Joseph Ratzinger, the pope spent much of his life in the country’s academic milieu; as he spoke to a gathering of scientists in the hall, he reminisced about his teaching days at the University of Bonn. “There was a lively exchange with historians, philosophers, philologists ...” Benedict said early in an address on faith and reason. Citing a conversation between a 14th-century Christian Byzantine emperor and an Islamic Persian, Benedict quoted Manuel II: “‘Show me just what Mohammed brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.’”

Within days Benedict found the globe engaged in a “lively exchange,” but it was not, one suspects, the exchange the pope had in mind. The Pakistani parliament voted to condemn him; the leading Shiite cleric in Lebanon asked for a personal apology. “He is going down in history in the same category as leaders such as Hitler and Mussolini,” said Salih Kapusuz, the deputy head of Turkey’s governing party, and officials there suggested the pope should reconsider a trip planned for November.

The Vatican soon issued a grandly titled “Declaration Concerning Pope’s Regensburg Address.” “It was certainly not the intention of the Holy Father to undertake a comprehensive study of the jihad and of Muslim ideas on the subject, still less to offend the sensibilities of the Muslim faithful,” said papal spokesman Federico Lombardi. If the goal, in Lombardi’s words, had been to articulate “a clear and radical rejection of the religious motivation for violence,” then Benedict failed.

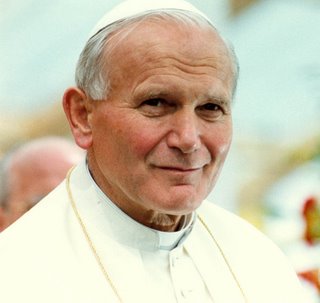

The pope’s intentions in discussing “holy war” were presumably good—he approvingly quoted an early Qu’ranic “surah” (chapter), which says “there is no compulsion in religion”—and he was right to raise the issue of how to confront and combat the religious extremism that gives rise to terror and violence. Sadly, though, he did so clumsily and obliquely, and, far from opening a constructive conversation, instead exacerbated tensions between Christianity and Islam. The episode also marks the first widely noted break with the spirit of the papacy of Benedict’s beloved predecessor. A reassuring pastor, John Paul II was the first pope to visit a mosque (in Damascus, Syria, in 2000), and he managed to project an air of ecumenicism while holding fast to the fundamentals of faith and doctrine. “This is clearly not John Paul II,” says R. Albert Mohler Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. “It’s a very different direction for the papacy, and reflects Benedict XVI’s worries about secularism, Islam and a declining Christian vigor in Europe.”

Much of the Regensburg address was a meditation on faith and reason, the roots of religiously inspired violence and the need for believers to see God as a figure of love. Roughly put, his argument was this: to Benedict, Islam’s conception of God so stresses God’s will that God can be understood to command the irrational.

For the pope, the Christian encounter with the classical world married faith and reason and thereby precluded, in principle, such misunderstandings of the nature of the God of Abraham, a nature that is, according to this argument, rooted in love and reason, not the will to dominance. Seen in such a light, “jihad,” which means “struggle,” can too easily be taken literally (as a call to violence against others) rather than figuratively (as many Muslim scholars argue it should be).

In the stormy aftermath of the address—on Saturday two churches in the West Bank were bombed—the Vatican argued that the real point of the lecture was to be found in this sentence: “A reason which is deaf to the divine and which relegates religion into the realm of subcultures,” Benedict said, “is incapable of entering into the dialogue of cultures.” In a post-Regensburg statement, Paul Cardinal Poupard, president of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, said, “Readers will find that this central theme is far more important than the introductory citation of the Emperor Manuel II ...”

Then why did Benedict quote the emperor in the first place? The most likely answer is that, no matter what the Vatican says now, the pope believes in having what the Catholic theologian and papal biographer George Weigel calls “a hard-headed conversation” about the role of faith in the life of the world. “He knew exactly what he was doing,” says Weigel. “He is saying that irrational violence is displeasing to God. The question Benedict is putting on the table is: ‘Does a significant part of Islam have the capacity to be self-critical?’ ”

Finding a way for the children of Abraham to live together in something approaching peace a perennial challenge, and Benedict understands that. “We must seek paths of reconciliation and learn to live with respect for each other’s identity,” he told a Muslim audience in Cologne last year. There was no such language at Regensburg. He did say Manuel II’s words were “startlingly brusque,” and made certain the audience understood he was reading a quotation, but the pope must have known his words would carry. And by speaking of jihad without alluding to Christianity’s dark history of violence in the name of God—the Crusades, forced conversions, pogroms, the Inquisition—Benedict seemed to be denouncing Islam while failing to acknowledge that any religion, including his own, can be manipulated and perverted to evil ends. “It is very hard to construe the pope’s remarks in a benign way,” says William A. Graham, the dean of the Harvard Divinity School. “Historically, there is no more basis for arguing that Islam is irrational than there is for arguing the same about Christianity or Judaism. In all three you can find tremendous discussion about revelation and reason, and there are people in all three who have landed outside the rational. Islam has bloody borders right now, but Christianity has certainly been bloody, as has Judaism in its more extreme forms.”

Two years before he became pope, Benedict published a book entitled “Truth and Tolerance,” in which he wrote that “religion demands the making of distinctions, distinctions between different forms of religion and distinctions within a religion itself, so as to find the way to its higher points.” One of the pities of Regensburg is that he made no such distinctions about Islam.

Is the ideology of hate that fuels Al Qaeda and its fellow travelers evil? Yes, it is, and too few Muslim leaders have spoken out against it in compelling and memorable terms. An Islamic reformation in which the young are educated to understand faith through critical thinking would, one hopes, push the forces of violence ever farther to the margins. History offers some consolation. “Islam spread far more thoroughly by proselytizing than by the sword,” says Graham. And the tradition most ruthlessly excluded in the first few centuries of the faith was one devoted to extreme violence, the Kharijites.

Going forward, the pope could usefully consult the words of another powerful Christian leader: “And given that Islam and Christianity worship the one God, Creator of heaven and earth, there is ample room for agreement and cooperation between them,” the leader said three months after September 11. “A clash ensues only when Islam or Christianity is misconstrued or manipulated for political or ideological ends.” The leader??

John Paul II.

من خلال اقتباسه كلام إمبراطور مسيحي من القرن الـ 14 حول إسلام »شرير وغير إنساني«، أثار بنديكتوس السادس عشر عاصفة عالمية. ماذا دهاه؟

حرب البابا المقدسة

كتب: جون ميشام

نيوزويك

نيوزويك

كان المشهد مألوفا والمناسبة مواتية، كما ظن الخطيب. في الساعة الثالثة من بعد ظهر يوم الثلاثاء الماضي، بعد جولة سريعة في السيارة البابوية عقب الغداء، بدأ بنديكتوس السادس عشر بإلقاء محاضرة في صالة ماغنا في جامعة ريغنسبورغ في ألمانيا. وكان جوزف راتسينغر، قبل أن يصبح بابا، قد أمضى الكثير من وقته في الوسط الأكاديمي في هذا البلد. وفي خطابه أمام حشد من العلماء في القاعة، راح يتذكر الأيام التي كان فيها أستاذا في جامعة بون. وقال البابا بنديكتوس في بداية خطابه عن الإيمان والعقل: "كان الجدال حادا مع المؤرخين والفلاسفة وعلماء فقه اللغة التاريخي..." ثم استشهد بحوار بين إمبراطور بيزنطي مسيحي من القرن الـ14 ومسلم فارسي، وقال بنديكتوس مقتبسا كلام مانويل الثاني: »أظهر لي ما الجديد الذي أتى به محمد، وسترى فيها فقط ما هو شرير وغير إنساني، مثل دعوته إلى نشر دينه بالسيف«".

في غضون أيام، وجد بنديكتوس العالم منشغلا في "جدال حاد"، لكنه لم يكن الجدال المنشود من قبل البابا. فقد صوت البرلمان الباكستاني على إدانته» وطالب المرجع الشيعي الأعلى في لبنان باعتذار شخصي. وقال صالح كابوسوز، نائب رئيس الحزب الحاكم في تركيا إن البابا "سيضعه التاريخ في الخانة نفسها مع قادة مثل هتلر وموسوليني"، واقترح المسؤولون هناك أن يعيد البابا النظر في رحلته إلى تركيا التي كانت مقررة في شهر نوفمبر.

وسرعان ما أصدر الفاتيكان بيانا يحمل العنوان البليغ »إعلان بشأن خطاب البابا في ريغنسبورغ«، قال فيه الناطق باسم البابا فيديريكو لومباردي: "لم يكن في نية الحبر الأعظم القيام بدراسة معمقة عن الجهاد والأفكار الإسلامية في هذا المجال، ولم تكن نيته إهانة المؤمنين المسلمين". فإن كان الهدف، التعبير عن "رفض واضح وجذري للدوافع الدينية وراء العنف" على حد كلام لومباردي، فإن بنديكتوس قد فشل.

كانت نوايا البابا من خلال تطرقه إلى "الحرب المقدسة" طيبة على الأرجح ــ لقد اقتبس آية قرآنية، تقول: "لا إكراه في الدين" ــئ؟ وكان محقا في إثارة كيفية مواجهة التطرف الديني الذي يؤدي إلى الإرهاب والعنف. لكن للأسف، فعل ذلك بطريقة خرقاء وغير مباشرة، وبدلا من فتح نقاش بناء، زاد من حدة التوتر بين المسيحية والإسلام. هذه الحادثة تشكل أول اختلاف ملحوظ مع سياسة سلفه المحبوب. فقد كان يوحنا بولص الثاني راعيا مطمئنا وكان أول بابا يزور مسجدا (في دمشق، بسوريا، عام 2000)، ونجح في نشر جو يحبذ التعاون بين الأديان من دون أن يتخلى عن أسس الإيمان والعقيدة. يقول آر آلبرت مولر جونيور، رئيس معهد اللاهوت المعمداني الجنوبي في لويفيل بولاية كنتاكي: "من الواضح أنه ليس كيوحنا بولص الثاني. البابوية تسلك منحى مختلفا جدا وتعكس قلق بنديكتوس السادس عشر بشأن العلمانية والإسلام وتراجع المسيحية في أوروبا".

وكان الكثير مما جاء في خطاب ريغنسبورغ تأملا حول الإيمان والعقل، وجذور العنف المستوحى من الدين، وضرورة أن يرى المؤمنون الله مثالا للمحبة. بعبارات مبسطة: بالنسبة إلى بنديكتوس، فإن نظرة الإسلام تشدد كثيرا على إرادة الله لدرجة أنه يبدو للبعض أن الأفعال غير العقلانية هي مشيئة الله. وبالنسبة إلى البابا، فإن احتكاك المسيحية بالنهضة التاريخية جمع بين الإيمان والعقل، وبالتالي حال مبدئيا دون إساءة فهم طبيعة الله، التي هي، وبحسب رأيه، مبنية على المحبة والعقل وليس على الرغبة في السيطرة. في ضوء ذلك، يمكن لمفهوم "الجهاد" أن يؤخذ حرفيا بسهولة (كدعوة إلى العنف ضد الآخرين) وليس بالمعنى المجازي (كما يرى الكثير من العلماء المسلمين أنه يجب أن يؤخذ).

وفي الأعقاب العاصفة لخطاب البابا ــ يوم السبت ألقيت متفجرات على كنيستين في الضفة الغربية ــ جادل الفاتيكان بأن المغزى الفعلي للمحاضرة يكمن في هذه الجملة: "المنطق الذي لا يصغي إلى تعاليم الله ويقسم الدين إلى ثقافات فرعية غير قادر على المشاركة في حوار الحضارات"، كما قال بنديكتوس. وفي بيان جاء بعد خطاب ريغنسبورغ، قال الكاردينال بول بوبارد، رئيس المجمع البابوي للحوار بين الأديان: "سيجد القراء أن هذه النقطة الأساسية أهم بكثير من الاقتباس عن الإمبراطور مانويل الثاني..."

إذن لماذا اقتبس بنديكتوس كلام الإمبراطور أصلا؟ الجواب على الأرجح هو أنه مهما قال الفاتيكان الآن، فإن البابا يود إقامة ما يسميه عالم اللاهوت الكاثوليكي وكاتب سيرة البابوات جورج ويغل "حوارا قاسيا" عن دور الإيمان في العالم. يقول ويغل: "كان يعرف تماما ما يفعله. إنه يقول إن العنف غير العقلاني يسيء إلى الله. والسؤال الذي يطرحه بنديكتوس: »هل تستطيع شريحة كبيرة من المسلمين القيام بنقد ذاتي؟«".

إن إيجاد طريقة لكي يتعايش أبناء إبراهيم فيما يشبه السلام يشكل تحديا دائما، وبنديكتوس يفهم ذلك. وقد قال لجمهور من المسلمين في كولونيا السنة الماضية: "علينا أن نسعى لإيجاد سبل تصالح وأن نتعلم احترام هوية الآخر". لكن لهجته كانت مختلفة في ريغنسبورغ. فقد قال إن كلام مانويل الثاني "فظ جدا"، وحرص على أن يفهم الجمهور أنه يقرأ اقتباسا، لكن لا بد أن البابا كان يعلم أن كلماته سيكون لها تأثير. ومن خلال كلامه عن الجهاد من دون التلميح إلى تاريخ المسيحية المليء بالعنف باسم الله ــ الحروب الصليبية، وإكراه الناس على اعتناق المسيحية، والمذابح، ومحاكم التفتيش ــ بدا أن بنديكتوس يشجب الإسلام من دون أن يقر بأن أية ديانة، بما فيها ديانته، يمكن تحويرها لأغراض شريرة. يقول ويليام أيه غراهام، عميد كلية اللاهوت في هارفارد: "من الصعب جدا تفسير كلام البابا بطريقة غير مسيئة. فتاريخيا، ليس هناك أسس للجدال بأن المسيحية واليهودية أكثر عقلانية من الإسلام. وفي الأديان الثلاثة، نجد جدالا كبيرا حول الوحي والعقلانية، وهناك أشخاص في الديانات الثلاث تخطوا نطاق العقلانية. هوامش الإسلام دامية الآن، لكن من المؤكد أن المسيحية كانت دامية، وكذلك اليهودية في أشكالها الأكثر تطرفا".

قبل سنتين من اعتلائه الكرسي البابوي، نشر بنديكتوس كتابا بعنوان Truth and Tolerance (الحقيقة والتسامح) كتب فيه أن "الدين يفرض علينا أن نميز بين مختلف أشكال الدين، وداخل الدين الواحد، لنجد أسمى ما فيه". ومن الأمور المؤسفة في خطابه في ريغنسبورغ أنه لم يتطرق إلى هذا التمييز فيما يتعلق بالإسلام.

هل إيديولوجية الكراهية التي تغذي تنظيم القاعدة والحركات المماثلة له شريرة؟ نعم، إنها كذلك، وقلة من القادة المسلمين شجبوها بعبارات مقنعة وبارزة. ومن شأن إصلاح إسلامي، حيث يتم تثقيف الشبان لفهم الإيمان من خلال التفكير الانتقادي، أن يهمش قوى العنف. والتاريخ يقدم بعض العزاء. يقول غراهام: "لقد انتشر الإسلام من خلال الارتداد عن ديانات أخرى أكثر منه عن طريق السيف". والطائفة الإسلامية التي نبذها الكثيرون في القرون الأولى هي التي كانت تكرس نفسها للعنف الشديد، أي طائفة الخوارج.

في المستقبل، قد يستفيد البابا من كلمات قائد مسيحي كبير آخر: "بما أن الإسلام والمسيحية يعبدان الإله الواحد، خالق السماء والأرض، فالمجال كبير للتوافق والتعاون بينهما. والصدام يحصل فقط عندما يساء فهم الإسلام أو المسيحية أو عندما يتم استغلالهما لأغراض سياسية أو إيديولوجية"، كما قال هذا القائد بعد مرور ثلاثة أشهر على هجمات 11 سبتمبر. فمن كان هذا القائد؟ إنه يوحنا بولص الثاني.

بمشاركة إدوارد بنتين في روما

تاريخ النشر: الثلاثاء 26/9/2006

في غضون أيام، وجد بنديكتوس العالم منشغلا في "جدال حاد"، لكنه لم يكن الجدال المنشود من قبل البابا. فقد صوت البرلمان الباكستاني على إدانته» وطالب المرجع الشيعي الأعلى في لبنان باعتذار شخصي. وقال صالح كابوسوز، نائب رئيس الحزب الحاكم في تركيا إن البابا "سيضعه التاريخ في الخانة نفسها مع قادة مثل هتلر وموسوليني"، واقترح المسؤولون هناك أن يعيد البابا النظر في رحلته إلى تركيا التي كانت مقررة في شهر نوفمبر.

وسرعان ما أصدر الفاتيكان بيانا يحمل العنوان البليغ »إعلان بشأن خطاب البابا في ريغنسبورغ«، قال فيه الناطق باسم البابا فيديريكو لومباردي: "لم يكن في نية الحبر الأعظم القيام بدراسة معمقة عن الجهاد والأفكار الإسلامية في هذا المجال، ولم تكن نيته إهانة المؤمنين المسلمين". فإن كان الهدف، التعبير عن "رفض واضح وجذري للدوافع الدينية وراء العنف" على حد كلام لومباردي، فإن بنديكتوس قد فشل.

كانت نوايا البابا من خلال تطرقه إلى "الحرب المقدسة" طيبة على الأرجح ــ لقد اقتبس آية قرآنية، تقول: "لا إكراه في الدين" ــئ؟ وكان محقا في إثارة كيفية مواجهة التطرف الديني الذي يؤدي إلى الإرهاب والعنف. لكن للأسف، فعل ذلك بطريقة خرقاء وغير مباشرة، وبدلا من فتح نقاش بناء، زاد من حدة التوتر بين المسيحية والإسلام. هذه الحادثة تشكل أول اختلاف ملحوظ مع سياسة سلفه المحبوب. فقد كان يوحنا بولص الثاني راعيا مطمئنا وكان أول بابا يزور مسجدا (في دمشق، بسوريا، عام 2000)، ونجح في نشر جو يحبذ التعاون بين الأديان من دون أن يتخلى عن أسس الإيمان والعقيدة. يقول آر آلبرت مولر جونيور، رئيس معهد اللاهوت المعمداني الجنوبي في لويفيل بولاية كنتاكي: "من الواضح أنه ليس كيوحنا بولص الثاني. البابوية تسلك منحى مختلفا جدا وتعكس قلق بنديكتوس السادس عشر بشأن العلمانية والإسلام وتراجع المسيحية في أوروبا".

وكان الكثير مما جاء في خطاب ريغنسبورغ تأملا حول الإيمان والعقل، وجذور العنف المستوحى من الدين، وضرورة أن يرى المؤمنون الله مثالا للمحبة. بعبارات مبسطة: بالنسبة إلى بنديكتوس، فإن نظرة الإسلام تشدد كثيرا على إرادة الله لدرجة أنه يبدو للبعض أن الأفعال غير العقلانية هي مشيئة الله. وبالنسبة إلى البابا، فإن احتكاك المسيحية بالنهضة التاريخية جمع بين الإيمان والعقل، وبالتالي حال مبدئيا دون إساءة فهم طبيعة الله، التي هي، وبحسب رأيه، مبنية على المحبة والعقل وليس على الرغبة في السيطرة. في ضوء ذلك، يمكن لمفهوم "الجهاد" أن يؤخذ حرفيا بسهولة (كدعوة إلى العنف ضد الآخرين) وليس بالمعنى المجازي (كما يرى الكثير من العلماء المسلمين أنه يجب أن يؤخذ).

وفي الأعقاب العاصفة لخطاب البابا ــ يوم السبت ألقيت متفجرات على كنيستين في الضفة الغربية ــ جادل الفاتيكان بأن المغزى الفعلي للمحاضرة يكمن في هذه الجملة: "المنطق الذي لا يصغي إلى تعاليم الله ويقسم الدين إلى ثقافات فرعية غير قادر على المشاركة في حوار الحضارات"، كما قال بنديكتوس. وفي بيان جاء بعد خطاب ريغنسبورغ، قال الكاردينال بول بوبارد، رئيس المجمع البابوي للحوار بين الأديان: "سيجد القراء أن هذه النقطة الأساسية أهم بكثير من الاقتباس عن الإمبراطور مانويل الثاني..."

إذن لماذا اقتبس بنديكتوس كلام الإمبراطور أصلا؟ الجواب على الأرجح هو أنه مهما قال الفاتيكان الآن، فإن البابا يود إقامة ما يسميه عالم اللاهوت الكاثوليكي وكاتب سيرة البابوات جورج ويغل "حوارا قاسيا" عن دور الإيمان في العالم. يقول ويغل: "كان يعرف تماما ما يفعله. إنه يقول إن العنف غير العقلاني يسيء إلى الله. والسؤال الذي يطرحه بنديكتوس: »هل تستطيع شريحة كبيرة من المسلمين القيام بنقد ذاتي؟«".

إن إيجاد طريقة لكي يتعايش أبناء إبراهيم فيما يشبه السلام يشكل تحديا دائما، وبنديكتوس يفهم ذلك. وقد قال لجمهور من المسلمين في كولونيا السنة الماضية: "علينا أن نسعى لإيجاد سبل تصالح وأن نتعلم احترام هوية الآخر". لكن لهجته كانت مختلفة في ريغنسبورغ. فقد قال إن كلام مانويل الثاني "فظ جدا"، وحرص على أن يفهم الجمهور أنه يقرأ اقتباسا، لكن لا بد أن البابا كان يعلم أن كلماته سيكون لها تأثير. ومن خلال كلامه عن الجهاد من دون التلميح إلى تاريخ المسيحية المليء بالعنف باسم الله ــ الحروب الصليبية، وإكراه الناس على اعتناق المسيحية، والمذابح، ومحاكم التفتيش ــ بدا أن بنديكتوس يشجب الإسلام من دون أن يقر بأن أية ديانة، بما فيها ديانته، يمكن تحويرها لأغراض شريرة. يقول ويليام أيه غراهام، عميد كلية اللاهوت في هارفارد: "من الصعب جدا تفسير كلام البابا بطريقة غير مسيئة. فتاريخيا، ليس هناك أسس للجدال بأن المسيحية واليهودية أكثر عقلانية من الإسلام. وفي الأديان الثلاثة، نجد جدالا كبيرا حول الوحي والعقلانية، وهناك أشخاص في الديانات الثلاث تخطوا نطاق العقلانية. هوامش الإسلام دامية الآن، لكن من المؤكد أن المسيحية كانت دامية، وكذلك اليهودية في أشكالها الأكثر تطرفا".

قبل سنتين من اعتلائه الكرسي البابوي، نشر بنديكتوس كتابا بعنوان Truth and Tolerance (الحقيقة والتسامح) كتب فيه أن "الدين يفرض علينا أن نميز بين مختلف أشكال الدين، وداخل الدين الواحد، لنجد أسمى ما فيه". ومن الأمور المؤسفة في خطابه في ريغنسبورغ أنه لم يتطرق إلى هذا التمييز فيما يتعلق بالإسلام.

هل إيديولوجية الكراهية التي تغذي تنظيم القاعدة والحركات المماثلة له شريرة؟ نعم، إنها كذلك، وقلة من القادة المسلمين شجبوها بعبارات مقنعة وبارزة. ومن شأن إصلاح إسلامي، حيث يتم تثقيف الشبان لفهم الإيمان من خلال التفكير الانتقادي، أن يهمش قوى العنف. والتاريخ يقدم بعض العزاء. يقول غراهام: "لقد انتشر الإسلام من خلال الارتداد عن ديانات أخرى أكثر منه عن طريق السيف". والطائفة الإسلامية التي نبذها الكثيرون في القرون الأولى هي التي كانت تكرس نفسها للعنف الشديد، أي طائفة الخوارج.

في المستقبل، قد يستفيد البابا من كلمات قائد مسيحي كبير آخر: "بما أن الإسلام والمسيحية يعبدان الإله الواحد، خالق السماء والأرض، فالمجال كبير للتوافق والتعاون بينهما. والصدام يحصل فقط عندما يساء فهم الإسلام أو المسيحية أو عندما يتم استغلالهما لأغراض سياسية أو إيديولوجية"، كما قال هذا القائد بعد مرور ثلاثة أشهر على هجمات 11 سبتمبر. فمن كان هذا القائد؟ إنه يوحنا بولص الثاني.

بمشاركة إدوارد بنتين في روما

تاريخ النشر: الثلاثاء 26/9/2006

Queted from Newsweek Magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment